The award-winning Creative Director with a thirst for ideas

Martin Galton’s is the kind of irrepressible creative spirit that always finds an outlet. He got his start in advertising as an Art Director at BBH, going on to found Hooper Galton (via a sojourn at Leagas Delaney as partner to actual Tim Delaney), which ran successfully for twelve years. Now, he’s at it again, establishing new agency Beehive. When he’s not winning every advertising award going (120 and counting…) he likes to relax by changing the face of poetry with his live event Bang Said the Gun. And did we mention illustration? Yes he does those too. And they’re great. Obviously.

You’re a Creative Director, a poet and an illustrator. The question is: do you have enough jobs?

To me it’s all the same thing. I don’t do anything different when I’m painting to when I’m writing an ad. It’s all generating creative thought.

The best bit of the job – of any job – whether it’s painting a picture, or writing an ad, or writing a poem – is the idea. Once I’ve had a good idea, that’s it.

Did you always know you wanted to be a professional creative?

When I was at school, I remember very clearly the advice I received from the careers advisor on what career I might take. The only thing he could recommend for me, and for most of us, was to try and get a job on the line at Ford’s car factory in Dagenham. And I just thought, that isn’t for me.

“when you look around the world, literally everything is about art”

I was only really interested in art. But art was, and probably still is, looked down on as a non-subject. And yet when you look around the world, at the room I’m sitting in now, literally everything is about art: the colours, the furniture, the pictures on the wall, the room itself – someone had to design those things. They’re artistic endeavours. So, art is probably the most important subject in the world, really. But it’s never given that sort of elevation. Anyway, I used to paint and draw, and eventually I decided that’s all I was really interested in.

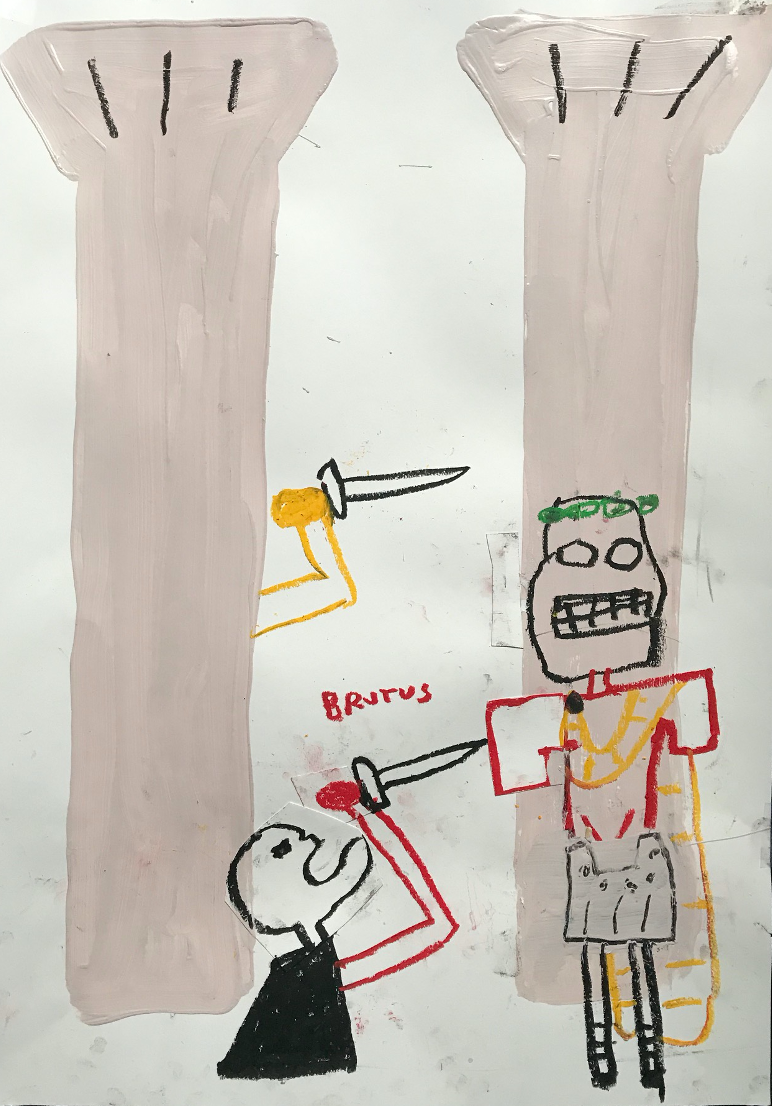

‘Early Knife Crime’ ©Martin Galton

How did you get your start in advertising?

It was almost impossible to get a job in advertising anywhere – we’d just come out of the Three-Day Week, and it was a bit like now – jobs weren’t plentiful. BBH was new at the time – only about a year old – but it was the hottest shop in town. I’d heard that they were about to win Asda, and I thought that if they were about to win a big retail account they’d need to hire some people. So I went to Asda and bought five loaves and two fishes. I attached a little label to the carrier bag that said ‘I may not be able to work miracles, but for Asda I could be Heaven-sent’ and left it on the door of their office. Within the hour they’d won Asda, and John Hegarty rang me immediately. I went in with my portfolio, which was rubbish, by the way. But he sent me away saying,

‘We don’t know what we’re going to do with Asda yet. If you have any ideas, let me know.’

I went away for about a month and came back with posters, movie scripts – the lot. It was all crap. But somewhere in there was the line ‘You’d be off your trolley to go anywhere else.’ There were no emails back then so he sent me a letter asking me to come and see him at seven o’clock one morning. So I went to see him at seven o’clock and I sat in his office and he said,

‘I like your line. I’d like to use it, so I feel compelled to give you a job. When can you start?’ I said,

‘Right now. This second.’

You were an Art Director, but you’ve also written many ads. How did you begin writing for advertising?

I soon discovered that Art Directors were viewed within agencies as the thick ones. I was so angry about it that I wrote a series of radio commercials for Swinton Insurance. They were very good, and won every award going. After that I wasn’t seen as the thick one anymore, and in the process I also realised that I could write and that I really enjoyed it.

And what about poetry?

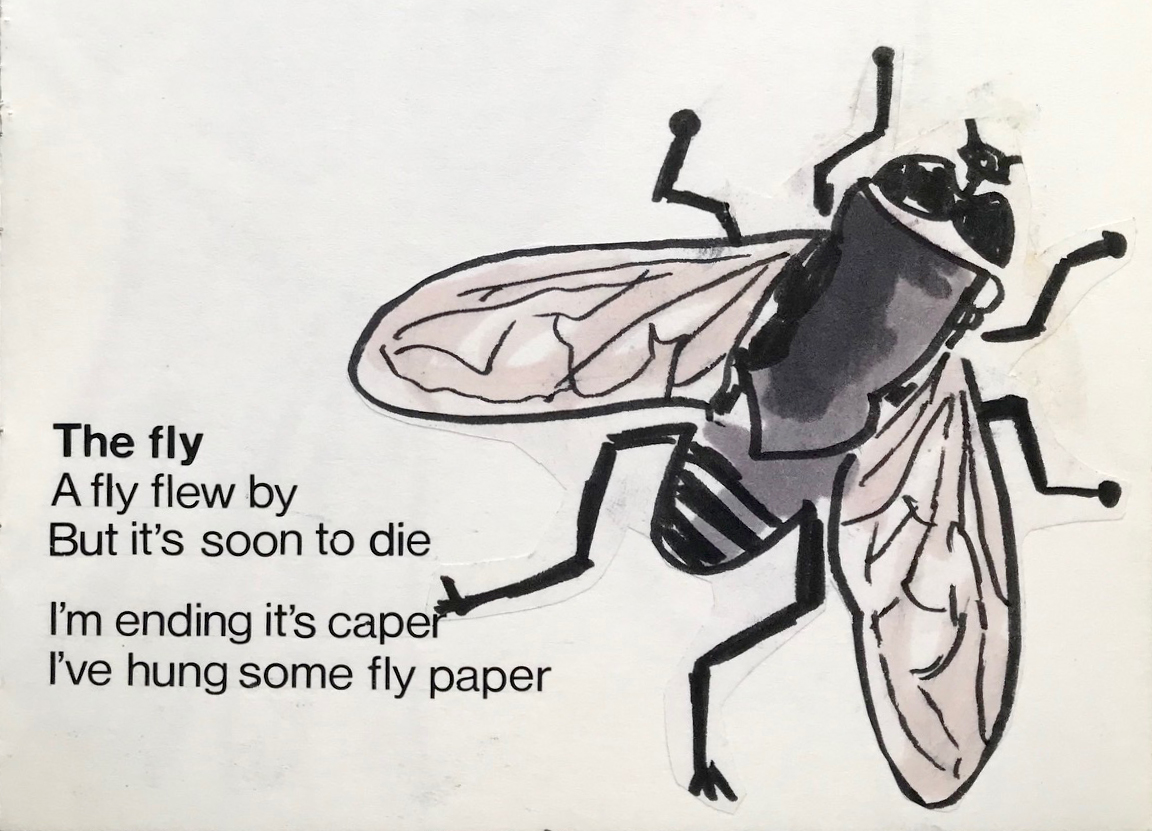

I’ve always written poetry. I wrote and illustrated my first poetry book at 11 years old.

A poem by Martin Galton, 11½ years old

But it was a friend – Dan Cockrill – who inspired me to create Bang Said The Gun. As Adrian Mitchell said, ‘Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people’, but I went to see Dan perform, and his poems were immediate and honest – they were more like lyrics to a song. I thought ‘I want to do that.’ So I set up Bang Said The Gun with Dan. At the time all poetry nights were stultifying dull. I called it stand-up poetry because I wanted to dispel ‘the P-word’; it’s a very loud and raucous night. We added music, we gave it a look and a feel, have games and all sorts of things that poetry nights don’t do. It took time for it to grow, but to do poetry, to write poetry, that appealed to the masses, seemed to me a great thing to do. It’s very straight and very to the bone what I try and do, with the night and with my own poems.

I wish.

by Martin Galton

I wish I had a Sylvia Plath 4-wheel drive.

I would drive it across rugged wordscapes

surrounded by the exploding seas of my mind

to find the most dramatic words

to describe how much I love you.

I wish I had a John Hegley 2.3 hatchback.

I’d fill it to the hilt

with laughter and madness

and drive to the country with you by my side

and picnic on the sweet fruits of your mind.

I wish I had a John Cooper Clark convertible.

It would make me more flashy and dashy

and the music would be loud and pulsating

as it was in my head

on the first day I saw you.

I wish I had a William Wordsworth transit van.

I would load it up with daffodils to bring colour

and the heady smell of promise

to my life

just as they do to a dormant garden.

I wish I could choose the car I drive

but life handed me a Ford Mondeo.

So – I filled it up with a tank full of love

and parked it outside your life

and hoped I would never get towed away.

Is that how you approach advertising as well?

If you talk to John Hegarty, he’ll tell you advertising is about the art of reduction: reducing things down to their simplest form. Because simple things are powerful things. You’ve only got to look at Charles Bukowski’s poems to see it. There’s not a spare word, syllable, comma or full stop, and his work is powerful because of it.

The thing is, creativity is a messy business. Ideas come out in all sorts of ways that aren’t always obvious or clear. It’s about spotting it, dissecting it and reducing it.

“creativity is a messy business”

Are there any campaigns from your own career that particularly stand out in your memory?

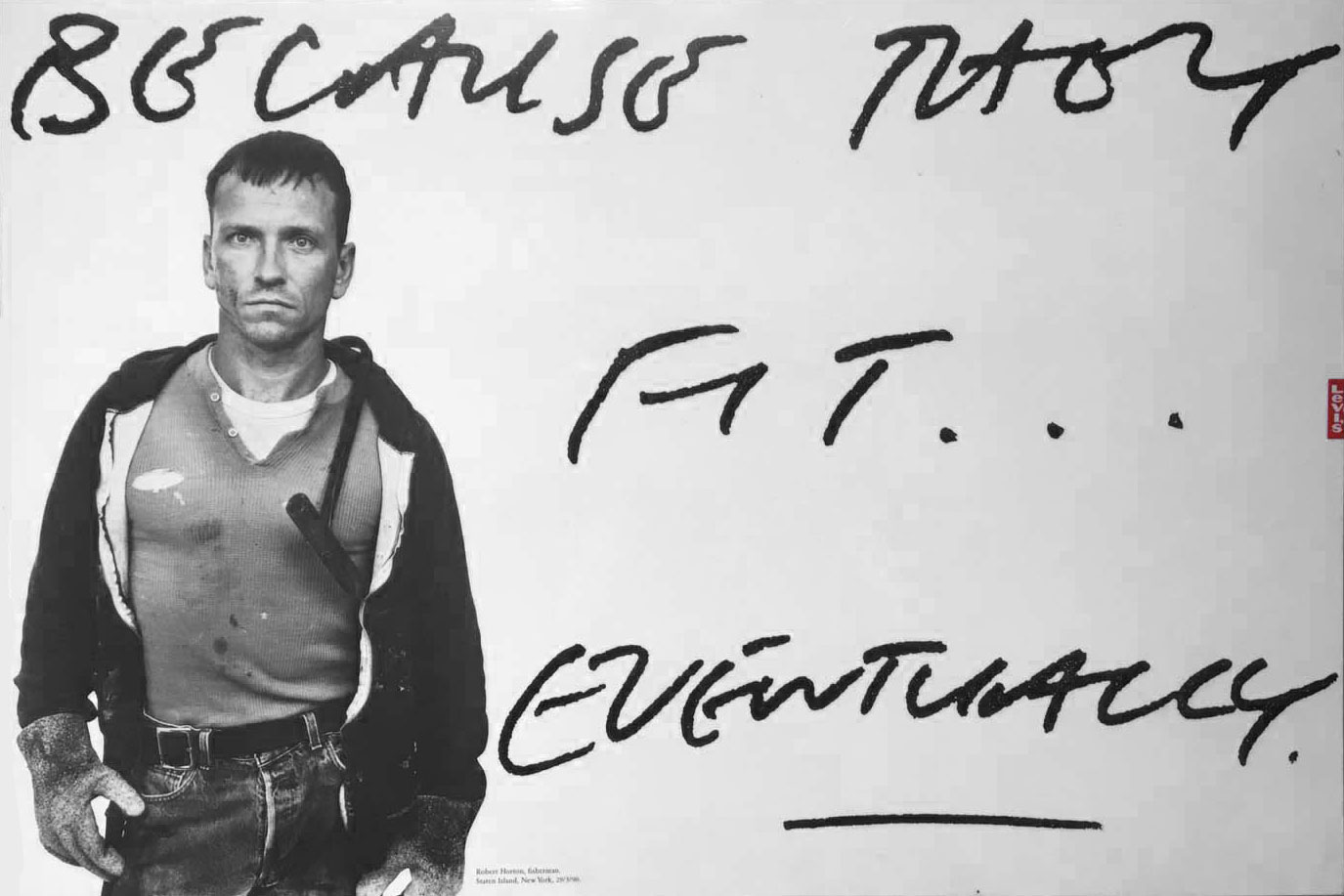

I think the best campaign I did with [then-copywriting partner] Will Awdry, was the Levi’s press campaign. They were very bold ads. We got Richard Avedon to shoot them, because I wanted them to look a bit like his American West portraits – simple, no artifice, almost startlingly clear. So I got to spend a week in New York working with him, and I found out the secret of how he takes his pictures. He sits down with his subject, talks to them, and he finds out the one thing that gets them really mad. Then he puts them in front of the camera and starts to talk about that one thing, and their whole demeanour drops, and that’s how he takes the picture. You can see right into the soul of the person, because the barrier is gone.

I also hadn’t seen handwriting on ads before, and putting big handwriting on an ad seemed to me like quite an outrageous thing to do.

Do you know when you’ve had a good idea?

Sometimes ideas grow on you. You have an idea and you think, well, that’s not very good, and then after a day or so, you can see something in it.

But I do have partners as well, people who are good sounding boards. I haven’t had a creative partner for… it must be 20 years, but with Beehive, I have a strategic partner, Tim Hollins, who I rely on heavily.

There’s nothing more thrilling than having a good idea. That’s where the spark comes from. I was listening to a footballer – I think it was Ian Wright – describing what it was like to score a goal, and the way he described it, well, I could actually feel it. It sounds like the most amazing thing, and that’s a bit like having an idea. Once you’ve got a brilliant idea, or what you think is a brilliant idea (often it isn’t), it’s very exciting – you just want to create it, to somehow make it live.

How do you feed that creative excitement?

I’m surrounded by brilliant things in the world. You’ve just got to walk round an art gallery, and you’ll be inspired by something. I can walk down the road and see a piece of graffiti and be inspired by it. Those are some of my reference points and I tend to bring those into the job.

How do you make sure your ideas are acting in service of the product and brief?

I think I’ve been trained very well by BBH. It’s a brilliant academy – I was very lucky to be there.

But, you don’t have to slavishly stick to a brief. It’s more about understanding the problem – once you’ve understood the problem, you can find a creative answer for it. Creatives love to say briefs are rubbish. But they’re not really. They’re as good as you’re going to get. A brief is just explaining a problem; it won’t give you the answer – it’s up to you to do that.

“if I’m wrong, I’m very happy to admit it, but you are being paid for your point of view”

And how do you make sure your ideas satisfy clients?

If a client really doesn’t like something and I believe they are wrong, I will fight for it. You’ve got to pick your battles, but if I believe I’m right, I get very passionate about it. Clients appreciate this enthusiasm for an idea more often than not. Christopher Ward Watches, who I’m working with now, is run by a really nice bloke called Mike France. And he basically says, ‘Look, I’ll go with you because I trust you – I trust your enthusiasm will make this work.’ And of course, once they’ve allowed you to do it, then they see it, and they go, ‘Oh yeah, you were right. Of course, you were.’ Sometimes you’ve got to stick to your guns.

And to be honest with you, if I’m wrong, I’m very happy to admit I’m wrong, but you are being paid for your point of view.

What prompted you to set up your new agency Beehive?

About two years ago, it dawned on me that agencies were largely fucked. Because clients are becoming more and more dissatisfied with how agencies work. They are slow; it’s hard for them not to be slow. They are expensive; they have to be expensive – they’ve got big offices and big salaries to pay. And often they’re not very creative.

Back in the eighties, most agencies were run by Creatives, and that isn’t the case anymore. Most agencies are run by account people. And because account people are very good at managing clients, they will not rock any boats. It seemed to me that we needed a new way of doing it. Because our emphasis is on actually making things, we have stripped away everything from the process you don’t need and left the things you do need: a creative person, a Planner, and a Producer. We describe ourselves as the agency alternative and bring other people in when we need them. This way we can be much more fleet of foot, much more cost-effective. And clients seem to be responding to it.

I don’t think big agencies will disappear, but I think there will be an alternative way of doing things. Ultimately, what we are trying to do is build something new out of an old legacy.

Martin Loves

Charles Bukowski’s book Ham on Rye

Adrian Mitchell’s poem Beattie is Three

The work of artist Roy Oxlade, who taught Martin

Black and white modern film masterpiece Bait

This poster from B&Q’s latest campaign

martingalton.com | workingbeehive.com | bangsaidthegun.com | Read Martin’s new book ‘How to Avoid Brand Bullshit’

Love this? Get more.